Psudeogenes That Can Be Activated Again

Pseudogenes are nonfunctional segments of Dna that resemble functional genes. Virtually arise as superfluous copies of functional genes, either straight past Deoxyribonucleic acid duplication or indirectly past reverse transcription of an mRNA transcript. Pseudogenes are normally identified when genome sequence analysis finds factor-like sequences that lack regulatory sequences needed for transcription or translation, or whose coding sequences are plainly defective due to frameshifts or premature stop codons.

About non-bacterial genomes comprise many pseudogenes, often as many as functional genes. This is not surprising, since diverse biological processes are expected to accidentally create pseudogenes, and there are no specialized mechanisms to remove them from genomes. Eventually pseudogenes may exist deleted from their genomes by chance DNA replication or DNA repair errors, or they may accumulate and so many mutational changes that they are no longer recognizable equally former genes. Assay of these degeneration events helps clarify the effects of not-selective processes in genomes.

Pseudogene sequences may be transcribed into RNA at low levels, due to promoter elements inherited from the bequeathed gene or arising past new mutations. Although most of these transcripts volition have no more functional significance than adventure transcripts from other parts of the genome, some accept given ascent to beneficial regulatory RNAs and new proteins.

Properties [edit]

Pseudogenes are usually characterized past a combination of homology to a known gene and loss of some functionality. That is, although every pseudogene has a DNA sequence that is similar to some functional gene, they are normally unable to produce functional final poly peptide products.[1] Pseudogenes are sometimes difficult to identify and characterize in genomes, considering the two requirements of homology and loss of functionality are usually implied through sequence alignments rather than biologically proven.

- Homology is implied by sequence identity between the DNA sequences of the pseudogene and parent factor. Afterwards aligning the ii sequences, the percentage of identical base pairs is computed. A high sequence identity means that information technology is highly likely that these 2 sequences diverged from a common ancestral sequence (are homologous), and highly unlikely that these two sequences have evolved independently (encounter Convergent development).

- Nonfunctionality tin can manifest itself in many ways. Ordinarily, a gene must go through several steps to a fully functional protein: Transcription, pre-mRNA processing, translation, and protein folding are all required parts of this process. If whatsoever of these steps fails, so the sequence may be considered nonfunctional. In high-throughput pseudogene identification, the virtually normally identified disablements are premature end codons and frameshifts, which most universally forestall the translation of a functional protein product.

Pseudogenes for RNA genes are usually more difficult to notice as they do not need to be translated and thus do not accept "reading frames".

Pseudogenes can complicate molecular genetic studies. For case, amplification of a cistron past PCR may simultaneously dilate a pseudogene that shares similar sequences. This is known as PCR bias or distension bias. Similarly, pseudogenes are sometimes annotated every bit genes in genome sequences.

Candy pseudogenes frequently pose a trouble for cistron prediction programs, frequently being misidentified as real genes or exons. It has been proposed that identification of candy pseudogenes can assistance ameliorate the accurateness of gene prediction methods.[2]

Recently 140 homo pseudogenes take been shown to be translated.[3] All the same, the function, if whatever, of the protein products is unknown.

Types and origin [edit]

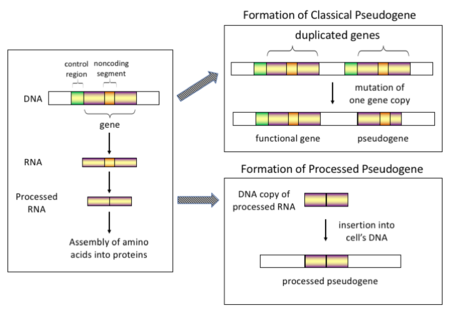

Mechanism of classical and processed pseudogene formation[4] [5]

There are four main types of pseudogenes, all with singled-out mechanisms of origin and characteristic features. The classifications of pseudogenes are as follows:

Processed [edit]

Candy pseudogene production

In higher eukaryotes, particularly mammals, retrotransposition is a fairly common result that has had a huge bear on on the composition of the genome. For example, somewhere between 30 and 44% of the human genome consists of repetitive elements such as SINEs and LINEs (come across retrotransposons).[half dozen] [7] In the process of retrotransposition, a portion of the mRNA or hnRNA transcript of a gene is spontaneously opposite transcribed dorsum into DNA and inserted into chromosomal DNA. Although retrotransposons usually create copies of themselves, it has been shown in an in vitro system that they tin create retrotransposed copies of random genes, likewise.[8] One time these pseudogenes are inserted dorsum into the genome, they usually contain a poly-A tail, and usually accept had their introns spliced out; these are both hallmark features of cDNAs. Even so, because they are derived from an RNA product, candy pseudogenes also lack the upstream promoters of normal genes; thus, they are considered "dead on arrival", becoming non-functional pseudogenes immediately upon the retrotransposition event.[9] Nevertheless, these insertions occasionally contribute exons to existing genes, commonly via alternatively spliced transcripts.[ten] A further characteristic of candy pseudogenes is common truncation of the 5' cease relative to the parent sequence, which is a event of the relatively not-processive retrotransposition mechanism that creates candy pseudogenes.[11] Processed pseudogenes are continually being created in primates.[12] Man populations, for case, have distinct sets of processed pseudogenes beyond its individuals.[xiii]

Non-processed [edit]

Ane style a pseudogene may arise

Non-candy (or duplicated) pseudogenes. Factor duplication is some other common and important process in the evolution of genomes. A copy of a functional factor may arise as a outcome of a gene duplication event acquired by homologous recombination at, for case, repetitive sine sequences on misaligned chromosomes and subsequently acquire mutations that cause the copy to lose the original gene's role. Duplicated pseudogenes usually have however characteristics as genes, including an intact exon-intron structure and regulatory sequences. The loss of a duplicated gene's functionality usually has little effect on an organism'south fitness, since an intact functional re-create notwithstanding exists. Co-ordinate to some evolutionary models, shared duplicated pseudogenes indicate the evolutionary relatedness of humans and the other primates.[14] If pseudogenization is due to factor duplication, it ordinarily occurs in the first few million years after the cistron duplication, provided the gene has not been subjected to any option pressure.[15] Gene duplication generates functional redundancy and it is non normally advantageous to conduct two identical genes. Mutations that disrupt either the structure or the part of either of the 2 genes are not deleterious and will non be removed through the selection process. As a issue, the gene that has been mutated gradually becomes a pseudogene and will be either unexpressed or functionless. This kind of evolutionary fate is shown past population genetic modeling[16] [17] and besides by genome analysis.[15] [18] According to evolutionary context, these pseudogenes will either be deleted or become and then distinct from the parental genes and then that they will no longer be identifiable. Relatively young pseudogenes can exist recognized due to their sequence similarity.[19]

Unitary pseudogenes [edit]

2 ways a pseudogene may be produced

Various mutations (such as indels and nonsense mutations) tin can prevent a factor from being unremarkably transcribed or translated, and thus the gene may get less- or non-functional or "deactivated". These are the same mechanisms by which non-processed genes become pseudogenes, only the deviation in this case is that the gene was not duplicated before pseudogenization. Normally, such a pseudogene would exist unlikely to go fixed in a population, only various population effects, such equally genetic drift, a population bottleneck, or, in some cases, natural pick, can lead to fixation. The classic example of a unitary pseudogene is the gene that presumably coded the enzyme Fifty-gulono-γ-lactone oxidase (GULO) in primates. In all mammals studied likewise primates (except guinea pigs), GULO aids in the biosynthesis of ascorbic acrid (vitamin C), only information technology exists every bit a disabled gene (GULOP) in humans and other primates.[twenty] [21] Some other more recent case of a disabled gene links the deactivation of the caspase 12 cistron (through a nonsense mutation) to positive selection in humans.[22]

Information technology has been shown that processed pseudogenes accrue mutations faster than non-processed pseudogenes.[23]

Pseudo-pseudogenes [edit]

The rapid proliferation of Deoxyribonucleic acid sequencing technologies has led to the identification of many apparent pseudogenes using cistron prediction techniques. Pseudogenes are frequently identified by the advent of a premature stop codon in a predicted mRNA sequence, which would, in theory, forestall synthesis (translation) of the normal poly peptide production of the original gene. There have been some reports of translational readthrough of such premature cease codons in mammals. Every bit alluded to in the effigy above, a minor amount of the protein production of such readthrough may still exist recognizable and function at some level. If so, the pseudogene can be subject to natural selection. That appears to have happened during the development of Drosophila species.

In 2016 it was reported that iv predicted pseudogenes in multiple Drosophila species actually encode proteins with biologically important functions,[24] "suggesting that such 'pseudo-pseudogenes' could represent a widespread phenomenon". For example, the functional poly peptide (an olfactory receptor) is found only in neurons. This finding of tissue-specific biologically-functional genes that could have been classified as pseudogenes by in silico analysis complicates the analysis of sequence data. In the human genome, a number of examples have been identified that were originally classified as pseudogenes but later on discovered to have a functional, although not necessarily protein-coding, role.[25] [26] As of 2012, information technology appeared that there are approximately 12,000–14,000 pseudogenes in the man genome,[27] A 2016 proteogenomics assay using mass spectrometry of peptides identified at least 19,262 homo proteins produced from sixteen,271 genes or clusters of genes, with eight new poly peptide-coding genes identified that were previously considered pseudogenes.[28]

Examples of pseudogene office [edit]

While the vast majority of pseudogenes have lost their office, some cases have emerged in which a pseudogene either re-gained its original or a like office or evolved a new function. Examples include the following.

Drosophila glutamate receptor. The term "pseudo-pseudogene" was coined for the cistron encoding the chemosensory ionotropic glutamate receptor Ir75a of Drosophila sechellia, which bears a premature termination codon (PTC) and was thus classified as a pseudogene. However, in vivo the D. sechellia Ir75a locus produces a functional receptor, owing to translational read-through of the PTC. Read-through is detected merely in neurons and depends on the nucleotide sequence downstream of the PTC.[24]

siRNAs. Some endogenous siRNAs appear to be derived from pseudogenes, and thus some pseudogenes play a part in regulating protein-coding transcripts, every bit reviewed.[29] One of the many examples is psiPPM1K. Processing of RNAs transcribed from psiPPM1K yield siRNAs that can act to suppress the virtually common blazon of liver cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma.[30] This and much other research has led to considerable excitement nearly the possibility of targeting pseudogenes with/every bit therapeutic agents[31]

piRNAs. Some piRNAs are derived from pseudogenes located in piRNA clusters.[32] Those piRNAs regulate genes via the piRNA pathway in mammalian testes and are crucial for limiting transposable element damage to the genome.[33]

BRAF pseudogene acts every bit a ceRNA

microRNAs. There are many reports of pseudogene transcripts interim as microRNA decoys. Perhaps the primeval definitive example of such a pseudogene involved in cancer is the pseudogene of BRAF. The BRAF gene is a proto-oncogene that, when mutated, is associated with many cancers. Normally, the corporeality of BRAF protein is kept under control in cells through the action of miRNA. In normal situations, the amount of RNA from BRAF and the pseudogene BRAFP1 compete for miRNA, but the remainder of the 2 RNAs is such that cells abound normally. Yet, when BRAFP1 RNA expression is increased (either experimentally or by natural mutations), less miRNA is available to control the expression of BRAF, and the increased amount of BRAF protein causes cancer.[34] This sort of contest for regulatory elements past RNAs that are endogenous to the genome has given rise to the term ceRNA.

PTEN. The PTEN gene is a known tumor suppressor gene. The PTEN pseudogene, PTENP1 is a processed pseudogene that is very similar in its genetic sequence to the wild-type cistron. Still, PTENP1 has a missense mutation which eliminates the codon for the initiating methionine and thus prevents translation of the normal PTEN protein.[35] In spite of that, PTENP1 appears to play a role in oncogenesis. The 3' UTR of PTENP1 mRNA functions as a decoy of PTEN mRNA by targeting micro RNAs due to its similarity to the PTEN gene, and overexpression of the 3' UTR resulted in an increment of PTEN poly peptide level.[36] That is, overexpression of the PTENP1 3' UTR leads to increased regulation and suppression of cancerous tumors. The biology of this organisation is basically the inverse of the BRAF system described above.

Potogenes. Pseudogenes can, over evolutionary fourth dimension scales, participate in cistron conversion and other mutational events that may give rise to new or newly functional genes. This has led to the concept that pseudo genes could be viewed as pot ogenes: pot ential genes for evolutionary diversification.[37]

Misidentified pseudogenes [edit]

Sometimes genes are thought to exist pseudogenes, usually based on bioinformatic analysis, but then turn out to be functional genes. Examples include the Drosophila jingwei gene[38] [39] which encodes a functional alcohol dehydrogenase enzyme in vivo.[forty]

Some other example is the human gene encoding phosphoglycerate mutase [41] which was thought to exist a pseudogene merely which turned out to exist a functional cistron,[42] now named PGAM4. Mutations in it crusade infertility.[43]

Bacterial pseudogenes [edit]

Pseudogenes are institute in bacteria.[44] Nearly are found in bacteria that are not free-living; that is, they are either symbionts or obligate intracellular parasites. Thus, they do not require many genes that are needed by gratuitous-living bacteria, such as gene associated with metabolism and DNA repair. All the same, there is not an lodge to which functional genes are lost first. For instance, the oldest pseudogenes in Mycobacterium leprae are in RNA polymerases and the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites while the oldest ones in Shigella flexneri and Shigella typhi are in DNA replication, recombination, and repair.[45]

The proS loci in Mycobacterium leprae and Thou. tuberculosis, showing 3 pseudogenes (indicated by crosses) in 1000. leprae that yet stand for functional genes in K. tuberculosis. Homologous genes are indicated by identical colors and vertical, hatched confined. Modified after Cole et al. 2001.[46]

Since most leaner that carry pseudogenes are either symbionts or obligate intracellular parasites, genome size somewhen reduces. An extreme example is the genome of Mycobacterium leprae, an obligate parasite and the causative agent of leprosy. It has been reported to have i,133 pseudogenes which give ascension to approximately 50% of its transcriptome.[45] The issue of pseudogenes and genome reduction can be further seen when compared to Mycobacterium marinum, a pathogen from the same family. Mycobacteirum marinum has a larger genome compared to Mycobacterium leprae because it can survive outside the host, therefore, the genome must contain the genes needed to do so.[47]

Although genome reduction focuses on what genes are not needed by getting rid of pseudogenes, selective pressures from the host tin can sway what is kept. In the case of a symbiont from the Verrucomicrobiota phylum, at that place are seven boosted copies of the cistron coding the mandelalide pathway.[48] The host, species from Lissoclinum, utilise mandelalides as part of its defence mechanism.[48]

The human relationship betwixt epistasis and the domino theory of gene loss was observed in Buchnera aphidicola. The domino theory suggests that if one gene of a cellular process becomes inactivated, then pick in other genes involved relaxes, leading to gene loss.[45] When comparing Buchnera aphidicola and Escherichia coli, information technology was constitute that positive epistasis furthers gene loss while negative epistasis hinders information technology.

See as well [edit]

- List of disabled homo pseudogenes

- Molecular evolution

- Molecular paleontology

- Pseudogene (database)

- Retroposon

- Retrotransposon

References [edit]

- ^ Mighell AJ, Smith NR, Robinson PA, Markham AF (February 2000). "Vertebrate pseudogenes". FEBS Letters. 468 (two–iii): 109–14. doi:x.1016/S0014-5793(00)01199-6. PMID 10692568. S2CID 42204036.

- ^ van Baren MJ, Brent MR (May 2006). "Iterative cistron prediction and pseudogene removal improves genome annotation". Genome Research. sixteen (5): 678–85. doi:10.1101/gr.4766206. PMC1457044. PMID 16651666.

- ^ Kim, MS; et al. (2014). "A draft map of the human proteome". Nature. 509 (7502): 575–581. Bibcode:2014Natur.509..575K. doi:ten.1038/nature13302. PMC4403737. PMID 24870542.

- ^ Max EE (1986). "Plagiarized Errors and Molecular Genetics". Creation Evolution Journal. 6 (3): 34–46.

- ^ Chandrasekaran C, Betrán East (2008). "Origins of new genes and pseudogenes". Nature Instruction. 1 (ane): 181.

- ^ Jurka J (December 2004). "Evolutionary impact of human Alu repetitive elements". Electric current Opinion in Genetics & Evolution. fourteen (half dozen): 603–eight. doi:ten.1016/j.gde.2004.08.008. PMID 15531153.

- ^ Dewannieux Yard, Heidmann T (2005). "LINEs, SINEs and processed pseudogenes: parasitic strategies for genome modeling". Cytogenetic and Genome Research. 110 (ane–4): 35–48. doi:10.1159/000084936. PMID 16093656. S2CID 25083962.

- ^ Dewannieux Thou, Esnault C, Heidmann T (September 2003). "LINE-mediated retrotransposition of marked Alu sequences". Nature Genetics. 35 (ane): 41–viii. doi:x.1038/ng1223. PMID 12897783. S2CID 32151696.

- ^ Graur D, Shuali Y, Li WH (Apr 1989). "Deletions in candy pseudogenes accumulate faster in rodents than in humans". Journal of Molecular Evolution. 28 (4): 279–85. Bibcode:1989JMolE..28..279G. doi:ten.1007/BF02103423. PMID 2499684. S2CID 22437436.

- ^ Baertsch R, Diekhans M, Kent WJ, Haussler D, Brosius J (Oct 2008). "Retrocopy contributions to the evolution of the human genome". BMC Genomics. 9: 466. doi:ten.1186/1471-2164-9-466. PMC2584115. PMID 18842134.

- ^ Pavlícek A, Paces J, Zíka R, Hejnar J (October 2002). "Length distribution of long interspersed nucleotide elements (LINEs) and processed pseudogenes of man endogenous retroviruses: implications for retrotransposition and pseudogene detection". Gene. 300 (i–ii): 189–94. doi:10.1016/S0378-1119(02)01047-eight. PMID 12468100.

- ^ Navarro FC, Galante PA (July 2015). "A Genome-Wide Landscape of Retrocopies in Primate Genomes". Genome Biology and Evolution. 7 (8): 2265–75. doi:10.1093/gbe/evv142. PMC4558860. PMID 26224704.

- ^ Schrider DR, Navarro FC, Galante PA, Parmigiani RB, Camargo AA, Hahn MW, de Souza SJ (2013-01-24). "Gene copy-number polymorphism caused by retrotransposition in humans". PLOS Genetics. 9 (1): e1003242. doi:10.1371/periodical.pgen.1003242. PMC3554589. PMID 23359205.

- ^ Max EE (2003-05-05). "Plagiarized Errors and Molecular Genetics". TalkOrigins Archive. Retrieved 2008-07-22 .

- ^ a b Lynch Chiliad, Conery JS (November 2000). "The evolutionary fate and consequences of indistinguishable genes". Science. 290 (5494): 1151–5. Bibcode:2000Sci...290.1151L. doi:ten.1126/science.290.5494.1151. PMID 11073452.

- ^ Walsh JB (Jan 1995). "How often practice duplicated genes evolve new functions?". Genetics. 139 (i): 421–viii. doi:10.1093/genetics/139.one.421. PMC1206338. PMID 7705642.

- ^ Lynch Yard, O'Hely Thousand, Walsh B, Force A (Dec 2001). "The probability of preservation of a newly arisen factor duplicate". Genetics. 159 (4): 1789–804. doi:x.1093/genetics/159.iv.1789. PMC1461922. PMID 11779815.

- ^ Harrison PM, Hegyi H, Balasubramanian S, Luscombe NM, Bertone P, Echols N, Johnson T, Gerstein Thou (February 2002). "Molecular fossils in the human genome: identification and analysis of the pseudogenes in chromosomes 21 and 22". Genome Enquiry. 12 (ii): 272–80. doi:10.1101/gr.207102. PMC155275. PMID 11827946.

- ^ Zhang J (2003). "Evolution by gene duplication: an update". Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 18 (6): 292–298. doi:10.1016/S0169-5347(03)00033-8.

- ^ Nishikimi M, Kawai T, Yagi Chiliad (Oct 1992). "Guinea pigs possess a highly mutated gene for 50-gulono-gamma-lactone oxidase, the primal enzyme for 50-ascorbic acrid biosynthesis missing in this species". The Periodical of Biological Chemical science. 267 (30): 21967–72. doi:x.1016/S0021-9258(xix)36707-9. PMID 1400507.

- ^ Nishikimi Yard, Fukuyama R, Minoshima S, Shimizu Northward, Yagi Yard (May 1994). "Cloning and chromosomal mapping of the human nonfunctional factor for L-gulono-gamma-lactone oxidase, the enzyme for Fifty-ascorbic acrid biosynthesis missing in human". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 269 (18): 13685–8. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(17)36884-nine. PMID 8175804.

- ^ Xue Y, Daly A, Yngvadottir B, Liu M, Coop M, Kim Y, Sabeti P, Chen Y, Stalker J, Huckle Eastward, Burton J, Leonard S, Rogers J, Tyler-Smith C (April 2006). "Spread of an inactive form of caspase-12 in humans is due to recent positive option". American Journal of Human Genetics. 78 (4): 659–70. doi:10.1086/503116. PMC1424700. PMID 16532395.

- ^ Zheng D, Frankish A, Baertsch R, Kapranov P, Reymond A, Choo SW, Lu Y, Denoeud F, Antonarakis SE, Snyder Yard, Ruan Y, Wei CL, Gingeras TR, Guigó R, Harrow J, Gerstein MB (June 2007). "Pseudogenes in the ENCODE regions: consensus note, assay of transcription, and development". Genome Research. 17 (6): 839–51. doi:x.1101/gr.5586307. PMC1891343. PMID 17568002.

- ^ a b Prieto-Godino LL, Rytz R, Bargeton B, Abuin Fifty, Arguello JR, Peraro Md, Benton R (November 2016). "Olfactory receptor pseudo-pseudogenes". Nature. 539 (7627): 93–97. Bibcode:2016Natur.539...93P. doi:10.1038/nature19824. PMC5164928. PMID 27776356.

- ^ Cheetham, Seth Due west.; Faulkner, Geoffrey J.; Dinger, Marcel E. (March 2020). "Overcoming challenges and dogmas to understand the functions of pseudogenes". Nature Reviews Genetics. 21 (3): 191–201. doi:10.1038/s41576-019-0196-i. PMID 31848477. S2CID 209393216.

- ^ Zerbino, Daniel R.; Frankish, Adam; Flicek, Paul (31 August 2020). "Progress, Challenges, and Surprises in Annotating the Human Genome". Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics. 21 (1): 55–79. doi:10.1146/annurev-genom-121119-083418. PMC7116059. PMID 32421357.

- ^ Pei B, Sisu C, Frankish A, Howald C, Habegger L, Mu XJ, Harte R, Balasubramanian S, Tanzer A, Diekhans Thou, Reymond A, Hubbard TJ, Harrow J, Gerstein MB (September 2012). "The GENCODE pseudogene resource". Genome Biology. 13 (9): R51. doi:10.1186/gb-2012-13-9-r51. PMC3491395. PMID 22951037.

- ^ Wright JC, Mudge J, Weisser H, Barzine MP, Gonzalez JM, Brazma A, Choudhary JS, Harrow J (June 2016). "Improving GENCODE reference gene notation using a high-stringency proteogenomics workflow". Nature Communications. 7: 11778. Bibcode:2016NatCo...711778W. doi:10.1038/ncomms11778. PMC4895710. PMID 27250503.

- ^ Chan WL, Chang JG (2014). "Pseudogene-derived endogenous siRNAs and their function". Pseudogenes. Methods in Molecular Biology. Vol. 1167. pp. 227–39. doi:10.1007/978-ane-4939-0835-6_15. ISBN978-1-4939-0834-9. PMID 24823781.

- ^ Chan WL, Yuo CY, Yang WK, Hung SY, Chang YS, Chiu CC, Yeh KT, Huang Hard disk, Chang JG (April 2013). "Transcribed pseudogene ψPPM1K generates endogenous siRNA to suppress oncogenic prison cell growth in hepatocellular carcinoma". Nucleic Acids Research. 41 (half-dozen): 3734–47. doi:10.1093/nar/gkt047. PMC3616710. PMID 23376929.

- ^ Roberts TC, Morris KV (December 2013). "Not so pseudo anymore: pseudogenes equally therapeutic targets". Pharmacogenomics. xiv (16): 2023–34. doi:10.2217/pgs.13.172. PMC4068744. PMID 24279857.

- ^ Olovnikov I, Le Thomas A, Aravin AA (2014). "A framework for piRNA cluster manipulation". PIWI-Interacting RNAs. Methods in Molecular Biology. Vol. 1093. pp. 47–58. doi:ten.1007/978-one-62703-694-8_5. ISBN978-1-62703-693-1. PMID 24178556.

- ^ Siomi MC, Sato Grand, Pezic D, Aravin AA (Apr 2011). "PIWI-interacting small RNAs: the vanguard of genome defence". Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 12 (four): 246–58. doi:10.1038/nrm3089. PMID 21427766. S2CID 5710813.

- ^ Karreth FA, Reschke M, Ruocco A, Ng C, Chapuy B, Léopold V, Sjoberg Grand, Keane TM, Verma A, Ala U, Tay Y, Wu D, Seitzer Northward, Velasco-Herrera Mdel C, Bothmer A, Fung J, Langellotto F, Rodig SJ, Elemento O, Shipp MA, Adams DJ, Chiarle R, Pandolfi PP (April 2015). "The BRAF pseudogene functions as a competitive endogenous RNA and induces lymphoma in vivo". Cell. 161 (two): 319–32. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2015.02.043. PMC6922011. PMID 25843629.

- ^ Dahia PL, FitzGerald MG, Zhang X, Marsh DJ, Zheng Z, Pietsch T, von Deimling A, Haluska FG, Haber DA, Eng C (May 1998). "A highly conserved processed PTEN pseudogene is located on chromosome band 9p21". Oncogene. 16 (18): 2403–half-dozen. doi:ten.1038/sj.onc.1201762. PMID 9620558.

- ^ Poliseno L, Salmena L, Zhang J, Carver B, Haveman WJ, Pandolfi PP (June 2010). "A coding-independent office of gene and pseudogene mRNAs regulates tumour biology". Nature. 465 (7301): 1033–viii. Bibcode:2010Natur.465.1033P. doi:10.1038/nature09144. PMC3206313. PMID 20577206.

- ^ Balakirev ES, Ayala FJ (2003). "Pseudogenes: are they "junk" or functional DNA?". Annual Review of Genetics. 37: 123–51. doi:10.1146/annurev.genet.37.040103.103949. PMID 14616058.

- ^ Jeffs P, Ashburner M (May 1991). "Processed pseudogenes in Drosophila". Proceedings: Biological Sciences. 244 (1310): 151–ix. Bibcode:1991RSPSB.244..151J. doi:x.1098/rspb.1991.0064. PMID 1679549. S2CID 1665885.

- ^ Wang Due west, Zhang J, Alvarez C, Llopart A, Long M (September 2000). "The origin of the Jingwei cistron and the complex modular structure of its parental cistron, yellow emperor, in Drosophila melanogaster". Molecular Biological science and Development. 17 (nine): 1294–301. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026413. PMID 10958846.

- ^ Long Chiliad, Langley CH (Apr 1993). "Natural selection and the origin of jingwei, a chimeric processed functional factor in Drosophila". Science. 260 (5104): 91–v. Bibcode:1993Sci...260...91L. doi:ten.1126/scientific discipline.7682012. PMID 7682012.

- ^ Dierick HA, Mercer JF, Glover TW (Oct 1997). "A phosphoglycerate mutase brain isoform (PGAM 1) pseudogene is localized inside the homo Menkes disease gene (ATP7 A)". Cistron. 198 (i–2): 37–41. doi:10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00289-viii. PMID 9370262.

- ^ Betrán E, Wang W, Jin L, Long M (May 2002). "Evolution of the phosphoglycerate mutase processed factor in human and chimpanzee revealing the origin of a new primate gene". Molecular Biology and Development. 19 (5): 654–63. doi:ten.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004124. PMID 11961099.

- ^ Okuda H, Tsujimura A, Irie S, Yamamoto K, Fukuhara South, Matsuoka Y, Takao T, Miyagawa Y, Nonomura N, Wada Thou, Tanaka H (2012). "A single nucleotide polymorphism inside the novel sex-linked testis-specific retrotransposed PGAM4 gene influences human male fertility". PLOS ONE. seven (5): e35195. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...735195O. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0035195. PMC3348931. PMID 22590500.

- ^ Goodhead I, Darby Air-conditioning (February 2015). "Taking the pseudo out of pseudogenes". Electric current Opinion in Microbiology. 23: 102–9. doi:ten.1016/j.mib.2014.xi.012. PMID 25461580.

- ^ a b c Dagan, Tal; Blekhman, Ran; Graur, Dan (xix Oct 2005). "The "Domino Theory" of Gene Death: Gradual and Mass Gene Extinction Events in Three Lineages of Obligate Symbiotic Bacterial Pathogens". Molecular Biological science and Evolution. 23 (2): 310–316. doi:10.1093/molbev/msj036. PMID 16237210.

- ^ Cole, Southward. T.; Eiglmeier, K.; Parkhill, J.; James, K. D.; Thomson, Northward. R.; Wheeler, P. R.; Honoré, Due north.; Garnier, T.; Churcher, C.; Harris, D.; Mungall, K. (2001-02-22). "Massive gene decay in the leprosy bacillus". Nature. 409 (6823): 1007–1011. doi:10.1038/35059006. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 11234002.

- ^ Malhotra, Sony; Vedithi, Sundeep Chaitanya; Blundell, Tom 50 (Baronial xxx, 2017). "Decoding the similarities and differences among mycobacterial species". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. xi (eight): e0005883. doi:10.1371/periodical.pntd.0005883. PMC5595346. PMID 28854187.

- ^ a b Lopera, Juan; Miller, Ian J; McPhail, Kerry 50; Kwan, Jason C (November 21, 2017). "Increased Biosynthetic Cistron Dosage in a Genome-Reduced Defensive Bacterial Symbiont". mSystems. ii (6): 1–18. doi:x.1128/msystems.00096-17. PMC5698493. PMID 29181447.

Further reading [edit]

- Gerstein M, Zheng D (Baronial 2006). "The existent life of pseudogenes". Scientific American. 295 (2): 48–55. Bibcode:2006SciAm.295b..48G. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0806-48. PMID 16866288.

- Torrents D, Suyama M, Zdobnov E, Bork P (December 2003). "A genome-wide survey of human pseudogenes". Genome Research. xiii (12): 2559–67. doi:10.1101/gr.1455503. PMC403797. PMID 14656963.

- Bischof JM, Chiang AP, Scheetz TE, Rock EM, Casavant TL, Sheffield VC, Braun TA (June 2006). "Genome-broad identification of pseudogenes capable of disease-causing factor conversion". Human being Mutation. 27 (6): 545–52. doi:10.1002/humu.20335. PMID 16671097. S2CID 20219423.

External links [edit]

- Pseudogene interaction database, miRNA-pseudogene and protein-pseudogene interaction maps database

- Yale University pseudogene database

- Hoppsigen database (homologous processed pseudogenes)

- RCPedia - Processed Pseudogene database

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pseudogene

0 Response to "Psudeogenes That Can Be Activated Again"

Post a Comment